I love reading about advertising in the early 20th century. It’s one of my favorite subjects, and it’s way too often neglected by the Internet at large.

Part of it is just a fascination with the ambition of those early admen. It was truly fitting for that age of great works. While bridges and skyscrapers were being built at breakneck speed (sometime literally), the admen were similarly constructing cultural edifices out of whole cloth, deciding almost singlehandedly what constituted a proper lunch, marriage proposal, or even morning ritual.

So much of what’s “normal” for us today was decided by executives on Madison Avenue 70 or 80 years ago that looking at that history is like getting a frontrow seat at the creation of the modern world.

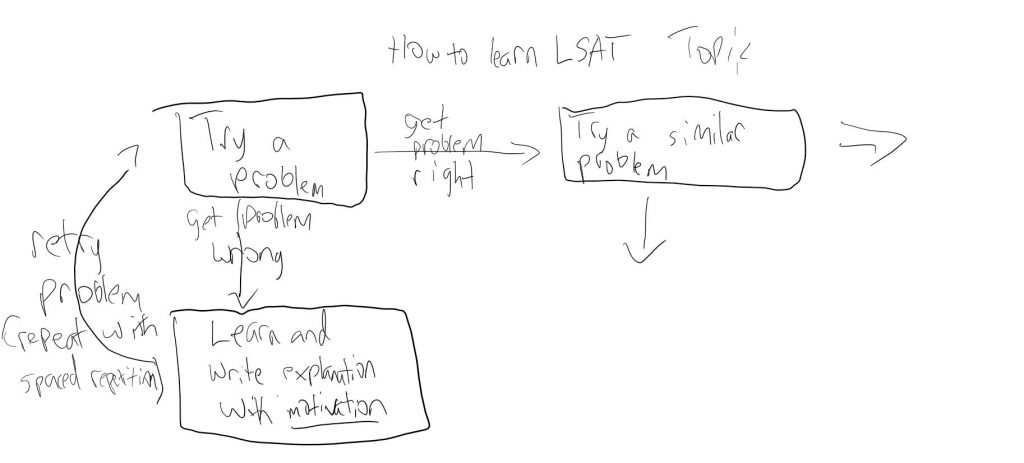

Another part of my fascination, however, is more practical. As I’ve studied these admen, I’ve found that their struggles and techniques for overcoming them have a resonance with my attempts to sell on the Internet today (i.e. my flashcard app for tutors and test-takers).

Early 20th century American capitalism was a no-holds-barred affair. Regulations were weak and a lot of the legal protections we take for granted today were nonexistent. Anyone could make any claim about their product, everyone was competing for everyone’s attention, and consumers weren’t particularly loyal to one brand or another. If you wanted someone to buy your soap, cereal, or toothpaste, you had to go out there and sell them on it.

Kind of similar to the Internet today, no? My flashcard app is, likewise, one of many. My app could easily get copied, slandered, or slated, and there’s not a lot I can do besides compete even more fiercely. I desperately want customers for it, but I know I will have to work incredibly hard for them.

The admen that survived and thrived in this environment were tough, resourceful, and occasionally unethical. More than anything, though, they were systematic, relentlessly experimenting to find effective marketing and copywriting techniques.

Ironically, just as their advertising campaigns passed into culture, so too have their innovative advertising techniques become part of the advertising landscape. It’s easy to not realize how innovative these techniques were until you look at the before and after, like how a plain description of pork and beans became a prime example of need-focused marketing.

Like most of the readers of this essay, though, I never actually learned this stuff. I had to learn all my marketing the hard way, by failing to sell things. Finding out the actual stories and laws of “scientific advertising” (itself a clever marketing phrase from that era) has made a huge difference in my ability to market myself and my products.

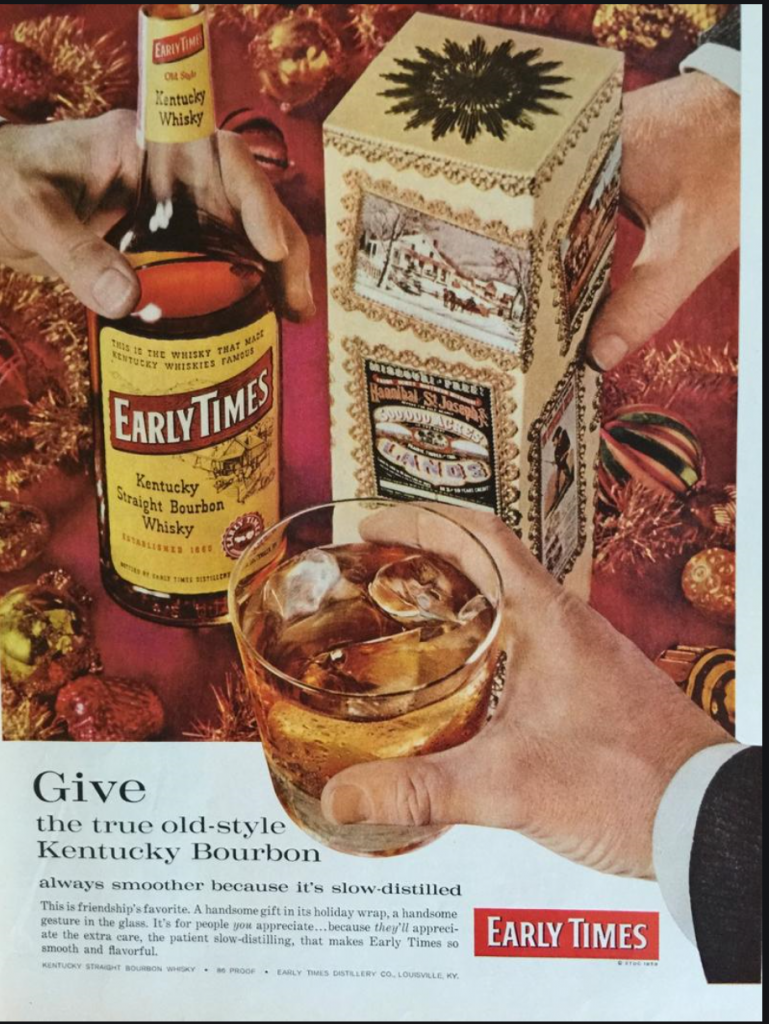

This is doubly so because my advertising looks a lot more like these old magazine ads than like modern television or magazine advertising. I employ hero images, headlines, and long copy to convince people to buy my products. I do not have the funds or resources to run a branding campaign, so these direct response campaigns are my main focus.

I’d like to share with you all the lessons that I learned from these early “Mad Men”. Hopefully, it’ll prove as useful to your marketing as it was to me.

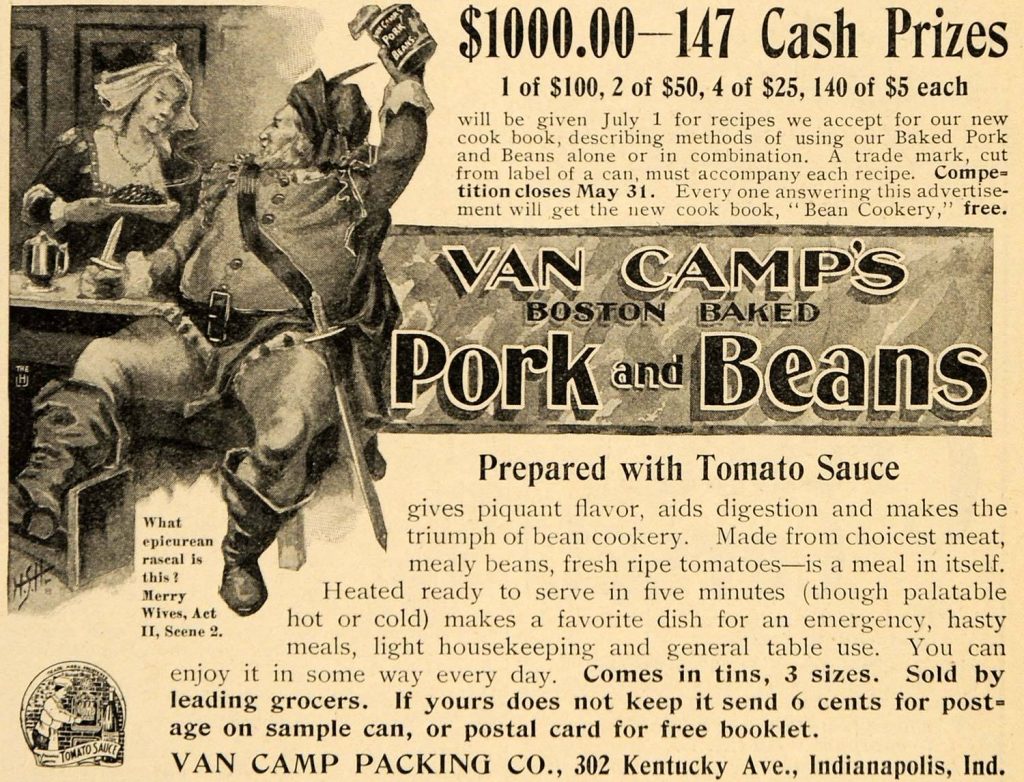

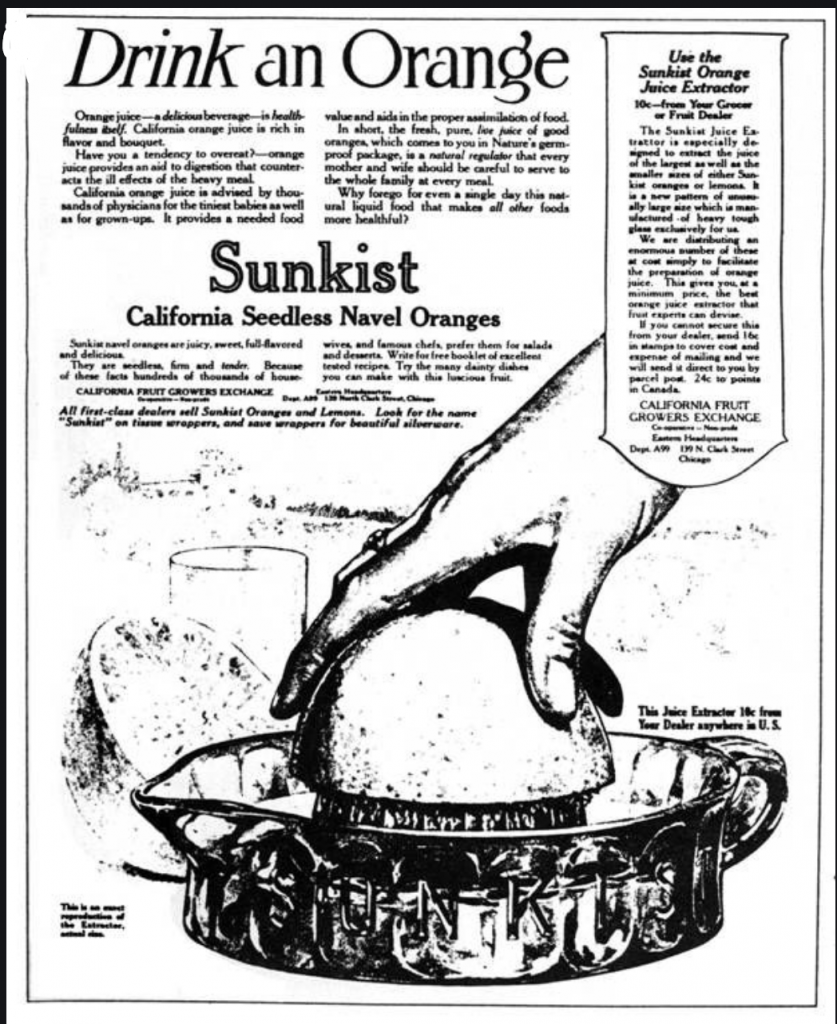

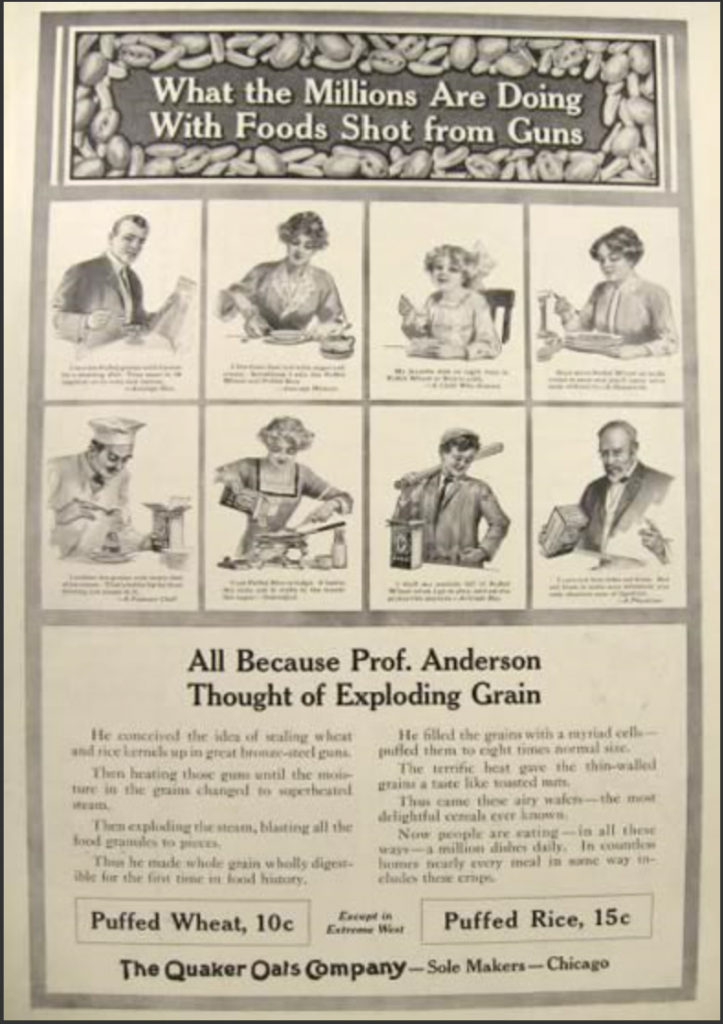

Before I start, this piece relies heavily on the work of Albert Lasker and his crew at Lord & Thomas: Claude Hopkins, John E. Kennedy, and the like. This is not only because these men were behind some of the greatest advertising successes of their age (Sunkist, Kotex, Puffed Wheat, the election of Warren G. Harding), but also convenience: they wrote a lot about what they did. In fact, Claude Hopkins literally wrote a book called Scientific Advertising, which I relied on for this piece along with Cruikshank’s and Schultz’s biography of Albert Lasker The Man Who Sold America.

Lesson 1: Measure campaigns (and measure sales especially).

The most important part of direct response copywriting is measuring the direct responses. Ideally, you measure all the way from first contact to point of sale.

For the early admen, this was tough. When they were just putting ads in magazines, they had literally no idea which ads were working and which ones weren’t. That’s why they made really heavy use of coupons.

For instance, in their campaign to turn Palmolive into the international juggernaut that it still is, they gave out coupons for 10 cent cakes of Palmolive. From there, they could measure the cost of the ad vs. the revenue. For instance, in Cleveland, their coupons cost $2000, their ads cost $1000, but sales increased from a base rate of $3000 per year to $20,000 per year after the campaign. Given that their ad campaign only ran in Cleveland and they had no other ads running at that time, they could tell that their ad campaign returned $14,000 on top of what they would have earned without the campaign (for details about this incredibly clever ad campaign, see footnote [1]).

Measuring is way easier in the Internet era, of course. With Google AdWords, segmentation tools, and Google Analytics it’s easy to see the result of a campaign. It’s shocking, then, that more Internet companies don’t measure their advertising, or worse, claim not to care. As Claude Hopkins would put it, “The only purpose of advertising is to make sales. It is profitable or unprofitable according to its actual sales.”

For my app, I care most about the funnel: from first click on my website, to trying out the app, to purchasing. Ironically, articles like this one aren’t actually great from a marketing standpoint (although good investments in SEO), as the people who will read this article are almost certainly not the same people who would purchase a flashcard app. Hopkins would accuse me of being more interested in artistry than sales, which he would be correct about. Oh, well.

Lesson 2: Samples and contests work, but only if people have to work for them

The admen at Lord and Thomas loved their free samples, coupons, and contests. However, they also quickly learned that you need to make people work for them.

For example, when they were first advertising puffed rice and puffed wheat (with the immortal tagline “Food shot from guns”), they made the mistake of distributing samples “promiscuously, like waifs”, which were quickly discarded by the consumers. Similarly, they mistakenly attempted to offer puffed wheat for free to anybody who bought puffed rice. As Lasker later put it, “it is just as hard to sell at a half price as at a full price to people who are not converted.”

Instead, the effective method was to make people work for it. If they wanted a free sample, they had to write a letter. If they wanted to guess the weight of the world’s biggest cake and win a prize, they had to buy a tin of Cotosuet, the lard substitute the cake was made with.

It’s a similar story today. Many websites do giveaways, especially venture-backed ones. It’s tempting as a way to juice sales or responses. But, it’s important to make your consumer work for the giveaway. If they don’t believe in the product enough to work for the giveaway, it’s a waste of time to give it to them.

This is something I’ve noticed as well. Whenever I just give away something (like a book, a video, or advice), I get poor quality responses and a lot of hassle. In other words, people treat the giveaway as worthless. But, even if I just require people to agree to sign up for my newsletter, people end up treating the giveaway with more care.

Lesson 3: Your headline needs to capture the most exciting part of your product.

While before we were talking about general marketing advice, now we can talk about copywriting specifically (like for your landing page).

It’s very common for people marketing on the Internet to feel like their headline needs to either reflect exactly what their product is, or their aspirations. That’s how you get generic headlines like “Connect with friends and the world around you on Facebook. ” or “A new way to manage your work” (from Monday.com).

Part of the problem, of course, is that space on the Internet is unlimited, and products on the Internet don’t face the intense pressure from competition that the products these admen were advertising. If you’re advertising a bar of soap, your headline has to be really attention-grabbing, because honestly soaps are pretty similar. If you’re advertising Facebook, not only do you get a ridiculous amount of free advertising and brand awareness, you’re also advertising a uniquely sticky product that seems to sell itself pretty darn well.

The admen didn’t have that luxury. They spent countless hours debating on the perfect headline, including punctuation and capitalization. Their headlines were attention grabbers: they made you want to read the ad and, crucially, buy the product (or send off for the sample).

So, they ended up with classic headlines like “A cow in your pantry” for evaporated milk, the aforementioned “food shot from guns” for puffed wheat and rice (it has to do with the manufacturing process), “Let this Machine do your Washing Free” [sic] for a hand-cranked washing machine, “Better than jewels — that schoolgirl complexion” for Palmolive “beauty soap”, and “Women like the convenience of Kotex” for the hitherto impossible to advertise for sanitary pads.

None of these were exact descriptions of was being sold, but they were exciting! Some of them were definitely oversold, like describing a hand-cranked washing machine like it was automatic, but they grabbed the reader’s attention and sold the product. The Palmolive headline is especially interesting: it doesn’t even sell the product, but the benefits of the product.

Similarly, if you want to sell products online, your headline needs to be something that captures the most exciting part of your product. I think Slack has an interesting take on this: “Slack replaces email inside your company.” For companies that have been drowning in email, it’s an appealing proposition.

Note that this headline does not actually describe what Slack does in any meaningful sense. This headline would also work for a personal whiteboard company (if they were really ambitious about the possibilities). But it addresses a specific problem and makes the reader want to find out more.

For my own app, I’ve decided on “Say goodbye to unproductive studying”. While it’s not quite as good as Lord & Thomas’s, it captures the benefits of my app pretty well, while still remaining intriguing.

Lesson 4: the core of copywriting is self-interest

This is something Claude Hopkins hammered home again and again. Copywriting (and marketing) should not be about winning awards or making art. At the end of the day, your copywriting is about communicating to the consumer why it benefits them to buy your product.

Too often copywriters think they have to win awards with their copywriting or entertain the reader. That’s nice, but that’s not what you’re aiming for. Your copywriting doesn’t need to be hilarious or heartwarming, it just needs to tell the reader why the product is to their benefit.

There’s another corollary to this, too: as long as you’re telling the reader as to why a product is to their benefit, it doesn’t matter how much you write. Again, going back to Claude Hopkins, “Some say, ‘Be but very brief. People will read but little.’ Would you tell that to a salesman?”

If you look at the early ads, like for Palmolive, it’s amazing how much text there is. This amount of text actually cost the advertisers more money, but they wrote as much as they needed to sell the product.

Nowadays, a lot of effective advertising has been replaced by video, which is even closer to salesmanship than longform text. Slack, for instance, puts a 2 and a half minute video on their homepage, along with around 100 words of text. If you look at someone like Tai Lopez, who is undoubtedly successful as a self-marketer (no comment on anything else), his videos selling his courses run over an hour in length.

There are still some practitioners of the art of the longform text sales page on the Internet, though. Brennan Dunn at Double Your Freelancing Rate does exactly that, as do a lot of the skeezy get-rich-quick guys who advertise on Facebook. I can’t say if their products perform as they promise, but their marketing obviously works, or else they wouldn’t keep running ads.

In your own marketing, don’t be afraid to write more and talk more. As long as your marketing keeps speaking to your customers’ self-interest (i.e. why your product will benefit them), they will keep reading. Or, as John E. Kennedy put it, “Copywriting is salesmanship in print.” As long as you’re still selling, keep talking.

My own landing page runs several hundred words in length. I’ve continually lengthened it over the months that it’s been up, and had good success with it. I’ve refined it based on the in-person communication I’ve had with people about my app, and what’s worked successfully in selling it. What works to sell in person also works to sell online.

Lesson 5: Marketing a product is about making the features seem extraordinary

There’s a classic Mad Men scene where Don Draper first figures out how to market Lucky Strike cigarettes: it’s toasted. The tobacco manufacturers are confused, because “everybody else’s tobacco is toasted”. Don Draper corrects him, “Everyone else’s tobacco is poisonous. Lucky Strike is toasted.”

This is an ad campaign that actually ran, masterminded by none other than Albert Lasker and his Lord & Thomas gang. The timeline in Mad Men is a bit messed up: that ad campaign was ran well before the cancer scare (it started in 1917), and wasn’t actually the most successful of the Lucky Strike campaigns (we’ll talk about that later).

But the core of the scene is correct. Making features seem extraordinary even when they were commonplace was a key technique of Lord & Thomas. For example, that’s exactly what Claude Hopkins did to sell Schlitz Beer. He created an advertising campaign called “poor beer vs. pure beer”, and claimed Schlitz’s “pure beer” was good for you because it was made with pure water, filtered air, and 4-times washed bottles. This was true of all beers, but as Hopkins put it, “Again and again I have told common facts, common to all makers in the line–too common to be told. But they have given the article first allied with them an exclusive and lasting prestige.” As a result, Schiltz went from 5th in sales to 2nd in sales in St. Louis, where the test campaign was run.

This technique is even more effective, however, when there is actually a cool new feature (and if you’re not willing to lie and say that a certain sort of beer is healthier for you). So, for instance, Lord & Thomas had a really hard time marketing Pepsodent, because it was pretty much identical to all other toothpastes. However, they had a lucky break when Pepsodent purchased the exclusive right to add sodium lauryl sulfate to their toothpaste, which is the ingredient that makes toothpaste foam.

So, how did Lord & Thomas capitalize on this lucky break? By calling out this new feature in the most ostentatious way possible. They couldn’t possibly call the new ingredient “Sodium Lauryl Sulfate”, so instead Lasker put out a challenge to Lord & Thomas employees: he wanted a 5 letter name with two consonants and three vowels. His employees came up with “irium”, which sounded suitably futuristic.

Then Lord & Thomas went buckwild. They rebranded Pepsodent as “Pepsodent with irium”. Having already been bankrolling Amos & Andy, the most popular show on radio, they flooded the airwaves with ads for new “Pepsodent with irium”. Pepsodent jumped to the top of toothpaste sales. And, to the delight of Albert Lasker, irium became so famous that the American Dental Association had to hire a receptionist specifically to talk to all the people who were calling in and asking about it.

In your own marketing, call out every single feature in your product and make it sound extraordinary. Describe it in loving detail and make up a name for it if you have to.

And remember: your customer is going to come to your product with a different view of what’s interesting than you are. My own product is a flashcard web app aimed at tutors and test-takers. Because it’s a web app, you can access it through your desktop or mobile browser. Duh, right?

Well, no. Pretty much every tutor I’ve talked to has been surprised and impressed to hear that. What is ordinary to me (and likely to you) is extraordinary to your customers. Treat it that way.

Lesson 6: The difference between a bug and a feature can be a matter of positioning

Sometimes bugs are just bugs. If you have an app that randomly shuts down at inopportune moments, that’s just something to be fixed.

However, sometimes bugs can be features for some users, as this immortal xkcd comic reminds us. In your marketing, you can make use of this.

This is what Lord & Thomas did when selling van Camp evaporated milk. They first got housewives to try it by advertising it as “a cow in your pantry”. However, they couldn’t get housewives to stick with it, because it tasted scalded (which, to be fair, it was). In other words, they didn’t have product-market fit, and advertising more was just going to burn through potential customers.

So they positioned it differently. They called it “sterilized milk”, and told housewives “you’ll know it’s genuine by its almond flavor”. The bug, bad taste, was transformed into a mark of cleanliness. In an era before strong food controls, that was a good marketing technique.

In your own marketing, you can do similar things. If you run a chat app, for instance, one of the main problems is that people feel such pressure to respond instantly that it totally distracts them from getting their work done. So, in your marketing, why not include a testimonial that suggests email is just too darn slow to have a proper conversation?

In other words, if your weaknesses are impossible to hide, might as well turn them into a strength.

Lesson 7: Fit your marketing in with existing habits

One of the first things Albert Lasker realized while helping to invent the modern marketing industry was that changing people’s habits with marketing was almost never profitable. The trouble was that you’d have to spend a lot of effort changing people’s habits, and then spend even more effort getting them to buy your product.

The better way was to identify a habit people already had, and exploit and popularize it with your marketing. People don’t want to just buy your product, they want to use it. If you tell them that they can use it to help them do what they already want to do, they’re a lot more likely to buy it.

Lord & Thomas exploited this constantly when they were tasked to sell fruit. They would promote recipes with the fruit, ways to use the fruit, and even, in the case of Sunkist oranges, manufactured juicers that were easier to use than the ones on the market to get people to make more orange juice.

However, their biggest success was with Lucky Strike cigarettes. They were successful with the “It’s toasted” campaign, but they still weren’t top of the market. The top of the market came when Lasker heard that doctors were prescribing cigarettes as appetite suppressants. So, he came up with the campaign, “Reach for a Lucky instead of a sweet.”

This was a classic case of exploiting existing habits. Lasker didn’t need to convince anyone that cigarettes worked as an appetite suppressant. He just needed to convince people to use a Lucky as a suppressant instead of another brand. This was so successful that sales increased by 8.3 billion units from 1928 to 1929, then reached 10 billion units in 1930.

In fact, this advertising campaign ended up being banned by the FTC because of complaints from candy manufacturers, so it was changed to just “Reach for a Lucky Instead”. At that point, the catchphrase was so ingrained that it still worked.

The best products, likewise, are positioned to fit in with existing habits. Slack couldn’t work as an email killer if people hadn’t already been using Gchat. Excel couldn’t work as well as it did if people hadn’t already been familiar with spreadsheets, and especially with Lotus 1-2-3. Every wildly successful product has been built on helping people do what they’re already doing, but easier.

In your own marketing, find what people are already doing and convince them that your product can help them do it easier and better. Don’t try to make them do something that they’re not already inclined to do.

In my own marketing, I’ve relied heavily on the existing popularity of spaced repetition flashcards like Anki and Quizlet. I have to convince users that my app is better than those, but not that the app is worthwhile at all.

Conclusion

You don’t have to reinvent the wheel. Marketing and selling have existed for hundreds of years, while modern marketing has existed for dozens.

The products being sold change, but the selling remain the same. Convince your customer that your product will benefit them, and they will listen to you and buy from you.

Footnotes

[1] The Palmolive campaign was actually incredibly clever. They needed to get Palmolive distributed in drug stores as a “beauty soap”, so it wouldn’t be competing against normal soap in general stores. In order to do so, they employed a carrot and a stick.

The carrot was that the copy of the ad claimed the drug stores were distributing essentially free samples of Palmolive (they paid 10 cents for them and the consumer was using a 10 cent coupon for them). However, in reality, the drug stores paid wholesale prices for the sample, and were reimbursed at retail prices by the manufacturer. The drug stores got the publicity of pretending to do a giveaway, while actually profiting.

The stick was that, before the coupons were sent out to consumers, they were sent out to all the drug stores in the area, along with a message that the coupons would surely be redeemed somewhere. The not so hidden message: if you don’t stock Palmolive yourself, be prepared to watch your customers form a line out the door of your competitiors.